Buried in the rate request that Illinois regulators cut last month from nearly $129 million to $73 million is the final phase of Ameren’s modernization efforts for its natural gas storage field just south of Freeburg.

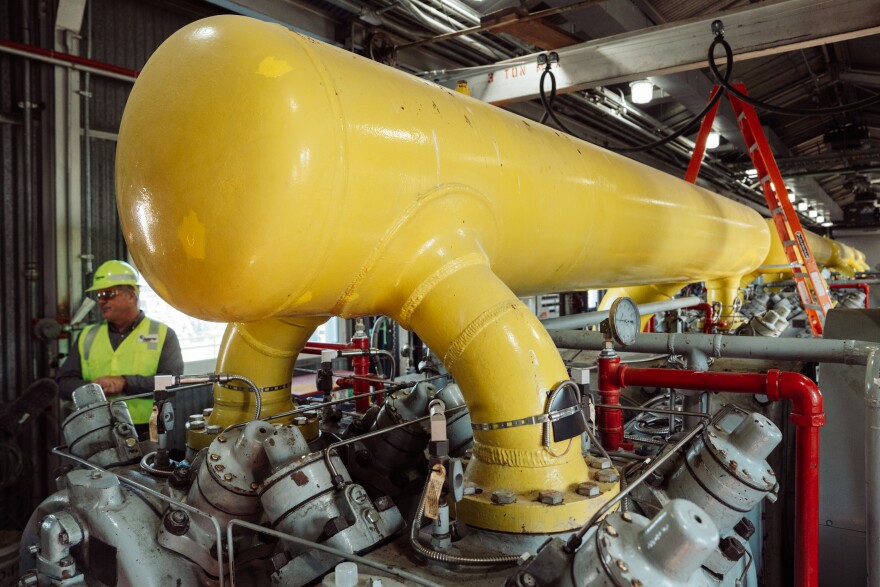

Since 2019, the utility company has been working toward transitioning seven of its 12 reservoirs, where Ameren stores billions of cubic feet of natural gas to be used in the colder months, from what’s known as vertical drilling to horizontal drilling.

This type of storage field requires a specific set of geological factors — mainly sandstone. Because the rock is so porous, Ameren can pump natural gas down hundreds of feet to be absorbed and stored.

Ameren borrowed the idea for horizontal drilling from natural gas production. Instead of just drilling vertically hundreds of feet down, the company drills down and then somewhat parallel to the ground — or horizontally — for another couple of thousand feet.

“You're exposing that wellhead to all of that additional pore space,” said Brad Kloeppel, Ameren Illinois’ senior director of gas technical services.

As more than 800,000 Illinoisans served by Ameren turn to natural gas to heat their houses and apartments with colder weather already hitting the region, the utility maintains that the modernization efforts underway at its storage sites near Freeburg and Centralia, among others, are needed.

“The business case is just so solid for these,” Kloeppel said. “Not only are we improving the health of the facility, which improves the reliability for our customers, we’re actually lowering our operating costs by doing this.”

While industry analysts that advocate for Illinois consumers contend this transition may be needed, they say these changes will be limited in their effectiveness to insulate ratepayers from price spikes.

“Based on what I know, this new technology will even help a little bit more,’’ said Abe Scarr, director of the Illinois Public Interest Research Group. “But, at the end of the day, if gas prices rise significantly, overall, there’s no amount of arbitrage that you can do that’s going to completely shield people from the ups and downs of gas prices, which tend to be volatile.”

These storage fields were originally built in the 1960s, Kloeppel said.

The effort in Freeburg, which has reduced Ameren’s physical footprint from 81 to 18 wells and from 4,600 to 10 acres, should be completed on schedule next year. However, similar efforts in Centralia could be delayed with the Illinois Commerce Commission’s recent ruling, according to Kloeppel.

The smaller footprint means maintenance is easier for the company, and farmers who own the land above the sandstone reservoirs don’t have to worry about Ameren equipment as much, Kloeppel said. The increased contact between the well and the reservoir allows Ameren to be more efficient in both injecting natural gas into sandstone and pulling it out to be shipped to customers.

“We can access more with less,” Kloeppel said.

In Illinois, energy companies can’t own energy production as they can in Missouri. Kloeppel and others joke that Ameren Illinois is just a “pipes and wires” company that delivers energy to customers.

All the natural gas shipped used by Illinois customers is purchased and shipped in via an extensive interstate network of pipelines from Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, Louisiana, Pennsylvania and even Canada.

These storage fields allow Ameren to insulate itself and customers from high natural gas costs seen in colder months when demand has skyrocketed, said Tim Eggers, Ameren’s director of gas storage in Illinois.

“If you're seeing those zero-degree temperatures, you're seeing the gas market very, very high — and that's when our value really shows itself,” Eggers said.

Near Freeburg, Ameren can store 1.9 billion cubic feet of natural gas hundreds of feet below the ground’s surface in porous sandstone. That’s enough to heat 30,000 homes annually, Eggers said.

Generally between November and March, Ameren will supplement 60% of the natural gas sent to homes all throughout their service area with stored gas that’s typically bought during warmer months at cheaper prices. The remaining 40% will come directly from the pipeline network — and can be far more expensive.

In late November, before the winter weather hit the St. Louis region, Ameren bought natural gas for $4.60 per million British thermal units. This summer, prices hovered around $3.

During the weekslong winter weather last January that left the region blanketed in ice, natural gas cost between $15 and $20.

During Winter Storm Uri in 2021, which led to major power outages across the U.S. and killed 246 people in Texas, prices reached $500 because of high demand. Ameren estimates the gas stored in its 12 fields across the state saved customers $100 million collectively during that storm.

“They're tremendous, tremendous value in defending against high market prices,” Eggers said of the storage fields.

The United States has enjoyed about a decade of relatively cheap natural gas due to higher levels of fracking and a subsequent increase in supply. However, Scarr believes that prices in the U.S. could be headed up in the future thanks to increased American exports and smaller inventories.

“There's some limits to how much this is going to protect consumers from the fluctuations of the gas market going forward,” he said.

Scarr and other consumer advocates have argued Illinois utility companies like Ameren have overinvested in their transmission infrastructure in their rate requests to the Illinois Commerce Commission. They’ve objected to the costs being passed onto consumers.

Last month's decision, for example, will result in a $3.65 increase on the monthly bill for the average residential customer in January.

However, the improvements to these storage facilities are not among those the consumer advocates have critiqued, Scarr said.

Illinois also committed to transitioning away from greenhouse gases when state lawmakers passed the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act in 2021. Given that Ameren owns both transmission for natural gas and electric, Scarr said the utility company could lead the way in that transition toward heating homes with electricity.

“If they lose a gas customer to somebody who electrifies that just means they're going to gain electric consumption by that same customer,” Scarr said.

Downstate Illinois, the territory Ameren serves, also has a slightly warmer climate than the Chicago area's, making it less burdensome to electrify, he said.

“Some level of investment is necessary, and we need to keep the gas system safe while we're using it,” Scarr said. “But we should really be reducing our investment in it — not increasing it.”