This article originally appeared in the St. Louis Beacon: The first time Ken Parker stepped onto the Saint Louis University campus was in November 1990, when he attended an academic conference there.

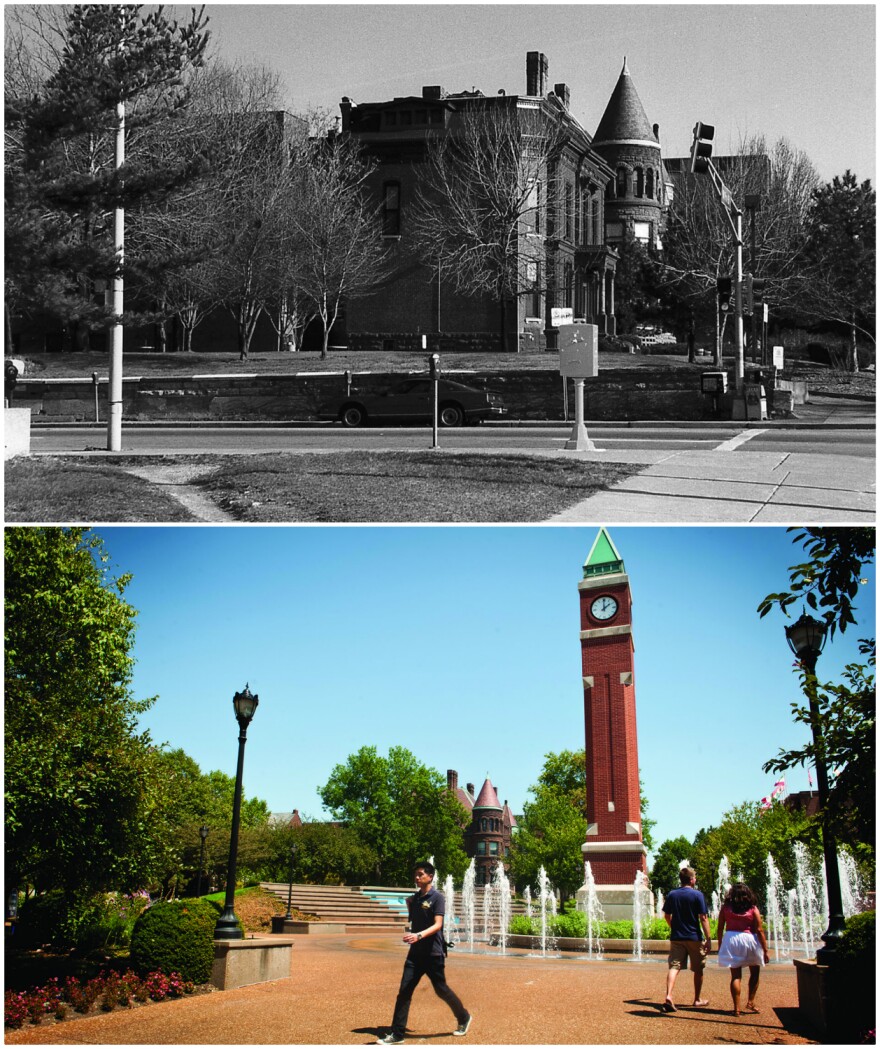

“I have a distinct memory of stepping out of the Busch Student Center,” he recalls, “looking across Grand and thinking, ‘I can’t imagine what it would be like to walk on this campus every day.’ It wasn’t a very attractive place.”

By the time he arrived two years later to join the university’s department of theological studies, “it was a very different place. A lot of the cosmetic changes had already happened.

“I remember a beautiful spring day in 1993, walking from my home in the Central West End to campus, with all of the flowers, and being very inspired by it. That’s one of my earliest memories of the place.”

The physical transformation of the SLU campus that Parker and so many others have found inspirational is the most tangible legacy of the Rev. Lawrence Biondi, who has announced his intention to retire as president of the university after serving for 25 years.

(Biondi himself has not responded to several requests by the Beacon for an interview.)

But for faculty members like Parker, who was active in the protests against Biondi’s leadership that resulted in no-confidence votes against him and demands for his ouster, some of the same traits and tactics that resulted in bricks-and-mortar success at SLU also undermined his credibility as an academic leader. His insistence on running a tightly controlled, centralized administration did not always lead to progress, they say.

“I was aware very early on that there was a pattern of broken promises,” Parker told the Beacon, relating concerns that were repeated in a series of interviews with members of the faculty – some of whom were reluctant to go on the record because they feared a backlash during Biondi’s remaining time as president.

“I was brought in by a chair of the department of theology who had been promised things to help facilitate the transformation of our Ph.D. program, taking it from a regional program to a program with an international profile. Many if not most of the promises made before I arrived were broken. Resources weren’t made available. Support was slow in coming.”

And as the campus became more attractive, and Biondi garnered the credit for the transformation, he became synonymous with SLU in the public’s mind. The close identification wasn’t always a good thing.

“He turned the campus around,” says Kathryn Kuhn, a professor of sociology who also was a vocal member of what many faculty members called “the alliance” acting against Biondi. “At the time he came, the campus was in an area that was considered to be unsafe, and he built it into what it is today. He built the endowment. He doubled the number of students. In many ways, he did embody the university, though that becomes a problem later, because people equate him with the university, and the university is more than any one person….

“There was such a cult of personality around him that people who could have served as sort of a reality check and could have played devil’s advocate with him all ended up leaving or not being there anymore, so he didn’t have anyone who would say, ‘Wait, let’s reconsider this.’ So many people equated Saint Louis University with Father Biondi, and he internalized that. People around him felt it unwise to challenge him too much, and things started spiraling out of control.”

A Grand vision

The one area where Biondi wins unqualified praise is the physical transformation he brought to SLU’s campus on Grand and to the Grand Center neighborhood just across Lindell. Statues have sprung up to be almost as plentiful as flowers, streets have been closed off to create more of a campus feel and attractive signage lets people know that this is Saint Louis University, not just a collection of midtown buildings that seem to have little relationship with each other.

“If you go back, there wasn’t a definition of either the campus or Grand Center,” recalls Vincent Schoemehl, the former three-term mayor of St. Louis who now is president and chief executive of Grand Center.

“I think his most important impact on Grand Center was the impact he had on the university, that it stabilized the edges and gave Grand Center the opportunity to create an arts district that would be the north flank of the campus. We couldn’t have done Grand Center if he had not done the campus the way he did.”

The way Biondi did the campus, says J. Joe Adorjan, now serving his third stint as chairman of the board of trustees at SLU, was by having a vision of what could be, then using his skills of persuasion to make it a reality.

“I can remember one time that we were standing on the top floor of Jesuit Hall, looking over that expanse at the corner of Grand and Lindell, where Mercantile Bank was,” Adorjan said in an interview. “He asked, ‘Who do we know at Mercantile? We have to talk to the bank. This could be a tremendous gateway to the campus.’”

Michael McMillan, who served for a decade as the alderman representing the area before being elected to his current post as license collector in the city, said that the man Biondi ended up working with on the project was Mercantile chairman and CEO Tom Jacobsen. Soon, the southeast corner of Grand and Lindell was cleared, making way for a fountain and a welcoming entrance to SLU.

“Jacobsen said he was relentless in pursuing his bank and property because he wanted the focus of his campus to be College Church,” McMillan told the Beacon. “Years ago, you would have never have thought that bank would have been acquired, demolished and turned into a fountain, but it’s a beautiful addition to the campus, and we were able to serve the banking needs of the community at the same time.”

McMillan, who noted his long history with SLU first as a student, then as an elected official, said the effort that Biondi made on the Mercantile project paid off in a big way, though he acknowledges that the president’s approach has its critics.

“I think Father Biondi has definitely been aggressive over time,” he said, “but what we have in the campus is worth the overall effort that has been put into the development. The campus we have now is capable of attracting people from across the country and the world.

“I think he has done a masterful job of creating a huge amount of infrastructure that has given Saint Louis University a national and international reputation for education excellence.”

And, adds Schoemehl, the campus beautification has had an almost immeasurable benefit for the neighborhood.

“The key to making Grand Center possible was the profound visual manifestation of the Saint Louis University campus,” he said. “All of a sudden, people said, 'This is where SLU is and this is where Grand Center is' and you could physically see it.”

Schoemehl also cited Biondi’s leadership in the redevelopment of the Continental Building at 3615 Olive.

“You couldn’t get anything done up here because no matter what you did, you had this 24-story building sitting there with trees growing on it,” he said.

Biondi’s leadership in getting tax breaks to spur development in the area was essential, Schoemehl said.

“This was a complicated, unprecedented neighborhood stabilization project,” he said. “Our TIF district takes in the entire north campus. If Father Biondi had not agreed to do that and not testified at the TIF commission, it just wouldn’t have happened.

“It wasn’t like SLU took half a billion dollars out of its endowment. They went and got us the tools so we could get half a billion dollars of investment.”

Academically, Schoemehl said, such investment made it possible to bring institutions like Cardinal Ritter Prep and the Grand Center Arts Academy to the area, enhancing Grand Center’s reputation. He compared it with well-defined campus areas like those at Harvard or the University of Chicago.

“Any place with a good academic reputation is also known as a place, a physically defined location where people can visualize the consequence of a vision,” Schoemehl said. “People didn’t know where Saint Louis University was in the mid-’80s. They knew where DuBourg Hall was. They knew where Pius Library was. They knew individual buildings, but there were all sorts of private owners in between.

“I don’t think you can create an environment where superior academics take place if you don’t have a visually compelling and safe academic environment. I think those two things are a prerequisite, and he did that.”

Did he do it in the right way? Talk of strong-arm tactics and tough bargaining has always been part of Biondi’s reputation – he has been branded “Father Capone,” referring to his Chicago heritage, and the campus has been termed “Fortress Biondi” -- but Schoemehl said such a reputation goes with the territory.

“You can never effect massive change without attracting critics,” he said. “It’s impossible. Your friends come and go, but your enemies accumulate. Over time, when you are running an institution like that, you aggravate somebody a little bit, then a little bit more with the next decision and a little bit more with the next decision, and pretty soon you cross over the line and they’re not with you any more.

“But you also have tens of thousands of students who graduated who are perfectly happy. They’re gone. Nobody interviews people who graduated from the university 15 years ago.”

From buildings to people

Those students may not be around any longer, but many members of the faculty at SLU who have been there for 15 years or longer say hopes were high that Biondi’s success at transforming the physical campus at SLU would spread to the academic side of the university as well. Those hopes, many say, never came to pass.

“If physical capital is Father Biondi’s greatest strength, human capital is his greatest weakness,” economics professor Bonnie Wilson, another leader in the faculty unrest that ultimately led to Biondi’s announcement to retire, wrote the Beacon in an email.

“That weakness is a key source of his decline and failure as president. Father Biondi bosses from behind, coercing through intimidation and with fear. Human capital requires leadership from the front, inspiring through encourage and with trust.”

Tim Lomperis, a political science professor who also has been an outspoken critic of Biondi’s leadership, recalls being recruited to the university as a department chairman from the outside in 1996, when Biondi had been president for nine years.

“There was a huge deal to make Saint Louis University the best Catholic university in America,” he said. He remembered an initiative called SLU 2000, which he said included $30 million for new professors, spending that was designed to do for academics what Biondi had been doing for the school’s physical campus.

“There was a whole new cadre of really crackerjack young scholars that really did promote much more of a research culture than had been the case before,” he said. “Department after department went up in rankings. It was supposed to have gone on for three years, but the trustees pulled it after the second year, and that kind of let the air out of the balloon of further attempts to improve SLU’s standing compared with other universities.”

Shortly after that, what may be considered the first hints of discontent with Biondi came from an uprising not of faculty but of students, angered by a sharp hike in parking fees on campus. According to a Riverfront Times article from 1999, hundreds of students marched on the SLU campus, chanting "Hey-hey, ho-ho, Father Biondi has got to go.”

In a preview of what was to occur more than a decade later, the Student Government Association voted no confidence in the university president; faculty members discussed a similar move but did not take a formal vote.

Category | 1986-1987 Academic Year | 2012-2013 Academic Year |

|---|---|---|

Total Student Body | 9,869 | 13,981 |

Size of the Freshman Class | 1,077 | 1,618 |

Students Living on Campus | 1,992 | 3,798 |

Endowment | $93 million | $970 million (as of April 15, 2013) |

Operating Revenue | $267 million | $704.4 million |

Avg. ACT Score of Freshman Class | 22.7 | 27.2 |

Student-Teacher Ratio | 16-1 | 12-1 (2011-2012 academic year) |

Number of Fulltime Ranked Faculty | 725 | 1,390 |

Endowed Chairs/Professorships | 16 | 65 |

Research Funding | $8.9 million | $51 million |

Size of Midtown Campus | 113 acres/62 buildings | 268 acres/131 buildings |

Provided by SLU

Still, the complaints about the president’s leadership style – autocratic, not collaborative, often impulsive, bordering on reckless – also foreshadowed what happened last fall when Manoj Patankar, Biondi’s hand-picked vice president for academic affairs, proposed a new system of post-tenure review that would have put SLU professors up for evaluation every six years.

“That mobilized the faculty like nothing else before,” Parker, the professor of theological studies, said. “His ability to divide and conquer was really quite successful until 2012.”

Met with strong opposition, the idea was quickly withdrawn, but no-confidence votes in Patankar – and eventually Biondi – were still approved by faculty and student groups. Many professors said the tenure changes were ill-advised and showed what the administration really thought of them – a disdain that they said had been building for a long time, as the administration often ignored professors’ advice despite the university’s stated policy of shared governance.

The attitude was often expressed in terms like “the cult of Biondi” and “a climate of fear” – a climate that persists despite the president’s announcement May 4 that he had asked the SLU board of trustees to begin the search for his successor. After Biondi acknowledged that his style could be labeled “my way or the highway,” that phrase became common when professors discussed the attitude from the president’s office.

And by refusing to share authority, he stifled growth. Lomperis put it this way:

“He’s axed some very competent and capable administrators. A president has to preside over a team of administrators that has authority to exercise. A university can’t run without strong provosts and strong deans. It certainly needs a strong president, and he’s been that, but he can’t just be that.

“This kind of concentration of all power in his person led to the collapse. No man has the capacity to run a 13,000-student university in as centralized a manner as he wanted to.”

Not that Biondi doesn't have his supporters on campus. One big backer is Mike Wolff, the newly named dean of the law school, who told the Beacon in an earlier interview that he doesn't share the view of many of his colleagues on campus of the president's way of running things.

“Father Biondi and the board of trustees are making a multimillion-dollar investment in the law school,” Wolff said. “I have a much different outlook than some of the arts and sciences folks, in part because I was here for quite a few years before Father Biondi ever came to this place. He has been a transformative presence, and he has taken an interest in the law school that has been very positive.”