A smartphone can tell you where to get a cup of coffee, but it can't go get the coffee for you. Engineers would like to build little machines that can do stuff. They would be useful for a lot more than coffee, if we could figure out how to make them work.

But the rules of mechanics change at small scales. Friction becomes dominant; turbulence can upend a small airplane.

"Gears and rotors and belts and pistons and all of the things that work really well at large scales, they just don't work at small scales," says Michael Dickinson, a zoologist at the University of Washington. One solution: insects.

Dickinson, who studies flies, says that insects are the ultimate micromachines: They've got acute sensors, superfast reflexes and lots of little moving parts. "Insects just excel at small," he says. "They really do small well."

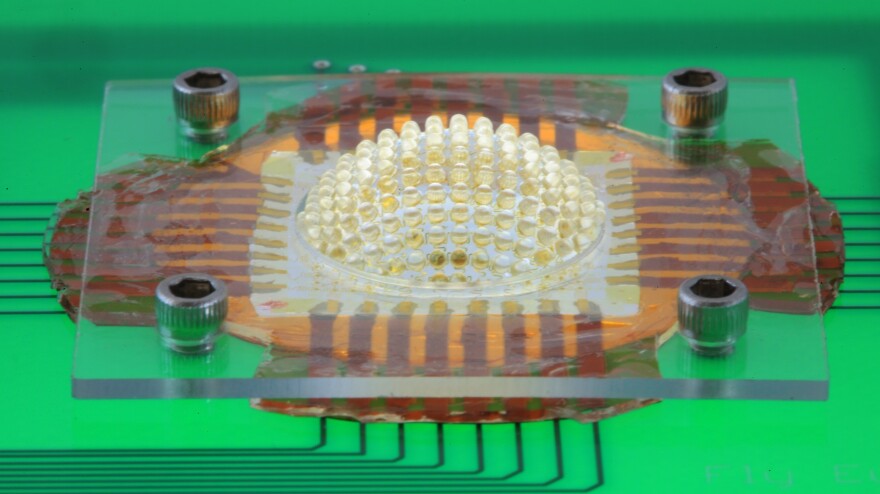

This week, two groups of engineers have unveiled two new machines that rip off insects. The first, published in the journal Nature, is a miniature camera. It looks just like a bug's compound eye, and works like one too. John Rogers, an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, developed the dime-sized camera by staring deep into the eyes of a bark beetle.

"It's just this amazing rainbow of colors and this amazing hemispherical shape in what is otherwise kind of an ugly beetle insect," he says. "And it only gets more interesting when you start to think about the details."

An insect's compound eye sees really well because each of its light-sensitive cells has its own dedicated lens. That means insect eyes have a huge field of view, are highly sensitive to motion, and keep everything in focus automatically. Copying that design lets Rogers' camera do things no other camera can, like view things over very wide angles without distortion. Rogers thinks his new camera could be used in hard-to-reach places. It could look inside the human body, for example, or be used for surveillance.

The second piece of insect imitation is published in the journal Science. Robert Wood at Harvard University has spent years trying to make miniature flying robots that could go do stuff in the world. Wood's flying robot copies real flies.

"If you just look at the aerial agility that flies have, it's quite astounding," Wood says. So it makes sense to try to replicate it.

The team built their robot by cutting flat pieces of different materials and sticking them together. Then they got the pieces to fold up into a robot. It took a while to get the little flybot working, Wood says.

"We would inevitably fly them and crash them, and fly them and crash them, and they would break," he says. Now the flies are able to stay aloft as long as 10 minutes or so (although they're still tethered by a cable for power and control).

Super-eyed fly robots could be used for all sorts of things. Individually, they might search through rubble of a collapsed building. A swarm of them might be used to help pollinate crops. With onboard batteries and microprocessors, they could network together to extend their reach and increase their intelligence.

Both projects still have a ways to go before they can really venture out on their own. In the meantime, zoologist Dickinson says that insects will continue to inspire engineers. And they should.

"It's been the age of insects for about 400 million years," Dickinson says. "So I think it's very appropriate to spend some of our energy trying to figure out how they work and sort of see the world from their perspective."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA1MjI2NzUxMDEyNzQyMTY5MjQ2YzkwNA004))