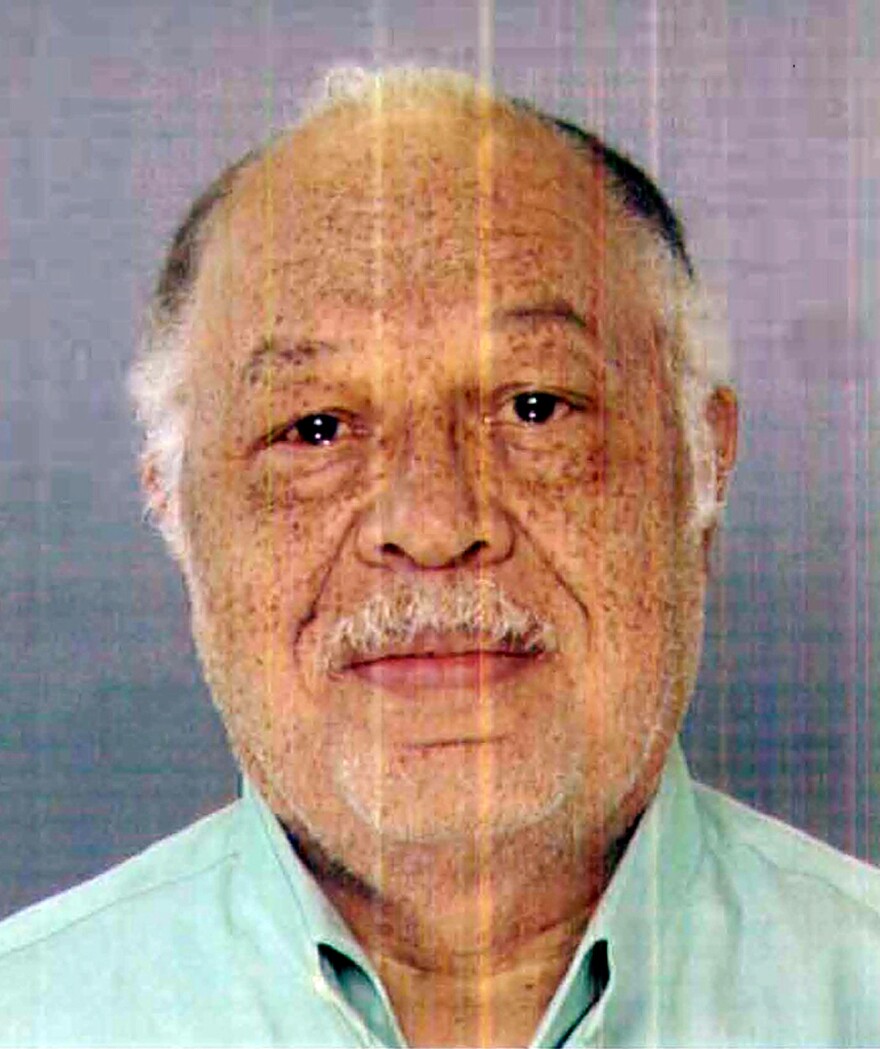

This is the sixth week of the trial of Dr. Kermit Gosnell, the physician charged with five counts of murder in the deaths of a woman and infants at the Philadelphia abortion clinic he owned and operated.

The case and its grisly details have prompted considerable debate about a variety of issues, including whether the media has covered it sufficiently.

But it has also laid bare some of the very issues at the heart of the still-simmering debate over abortion 40 years after the Supreme Court made it legal. Most directly, it raises the question of whether increasing regulation on abortion clinics make places like Gosnell's clinic more or less likely to exist.

One thing those on both sides of the abortion debate agree on is that what happened at the Women's Medical Society in West Philadelphia was unforgivable.

"It's such a horrific case," says Charmaine Yoest, president and CEO of the anti-abortion group Americans United for Life. "You see both the horrific destruction of innocent human life with the babies, but it also helps to illustrate our concern over how women are being treated in abortion clinics — as terrible commodities to increase the bottom line."

Carole Joffe, a sociology professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who has studied reproductive health issues since the 1970s, doesn't dispute that Gosnell was doing terrible things in his clinic and putting patients at risk.

"What Gosnell was doing was completely against the law," Joffe says, "and had there been any inspections, he would have been shut down a long time ago."

But where the two sides disagree, it's in the strongest of terms. Abortion opponents like Yoest, for example, say Gosnell is hardly the outlier those in the abortion-provider community say he is.

"This is a very dramatic case compared to what happens in some other clinics," she says. "But in all honesty, it doesn't completely surprise us because we've been trying to get attention to low-grade conditions in abortion clinics across the country for many many years."

That kind of rhetoric makes Joffe and her allies furious.

"Those opposed to abortion are trying to make the argument that all abortion providers are like Gosnell," she says, "which, of course, is absurd."

Joffe says a key reason Gosnell had patients in the first place is because the government doesn't pay for abortions for poor women. Even with its reputation for substandard care, Gosnell's clinic was all many poor women could afford.

"His prices were way under other prices in the area," Joffe says, citing the grand jury report in the case. "So, for example, he charged $330 for a first-trimester procedure; the prevailing rate at that time was approx $450."

And for low-income women, says Joffe, by the time they could come up with enough money for an abortion, often they were so far along in their pregnancy they either needed a more expensive, second-trimester procedure, or else they were beyond the legal limit. "And this leaves them vulnerable to places like Dr. Gosnell's clinic," she says, where he was allegedly performing the procedure beyond the time in pregnancy allowed by law.

For abortion opponents, the Gosnell case shows the need for more and stricter regulation.

"The fact that we regulate veterinary clinics and beauty parlors more than you do abortion clinics in this country, that's inexcusable," says Yoest. "And what it leads to is this kind of situation with Gosnell."

But abortion rights backers say the increasing restrictions end up giving women fewer choices other than substandard facilities like Gosnell's.

Joffe says a new Pennsylvania law passed in the wake of the Gosnell revelations has resulted in many abortion clinics that were providing perfectly safe care having to shut their doors.

"Pennsylvania used to have 22 facilities; now they have 13," she says. "The city of Pittsburgh used to have four clinics, now they're down to two."

There is one area where the two sides sort of agree: It's how politicized the issue has become.

The politics of abortion are hurting women who need access to safe and affordable abortions and can't get them, says Joffe. "Real women in the real world are suffering as this health care procedure becomes so incredibly politicized."

Yoest, meanwhile, says the power of what she calls "Big Abortion" is preventing common sense regulations.

"You create a political environment where politicians are unwilling to come anywhere near abortion clinics and that's untenable," Yoest says.

The trial of Gosnell, meanwhile, will go to jury deliberation next week. The defense ended abruptly Wednesday when the doctor chose not to testify and his lawyer presented no witnesses, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA1MjI2NzUxMDEyNzQyMTY5MjQ2YzkwNA004))