The director of the Missouri Department of Economic Development flipped through a slideshow at an October meeting about the future of power in the state. She landed on a slide showing large business projects the department is trying to attract to Missouri.

“I think this is the money slide, right?” said Michelle Hataway.

The slide displayed 10 data centers that the office is courting. Their peak electric demands were huge, reaching as high as 2,000MW, which is almost the entire output of Ameren Missouri’s largest power plant, the Labadie coal plant in Franklin County. In 2024, the largest single Ameren customer had a peak demand of 32MW.

“If you would have told me, whenever I became director of the department, that for an entire year I would be going around talking about power and the importance of power, I would have rolled my eyes and told you you're crazy, right?” Hataway said. “But that is where we are as a state.”

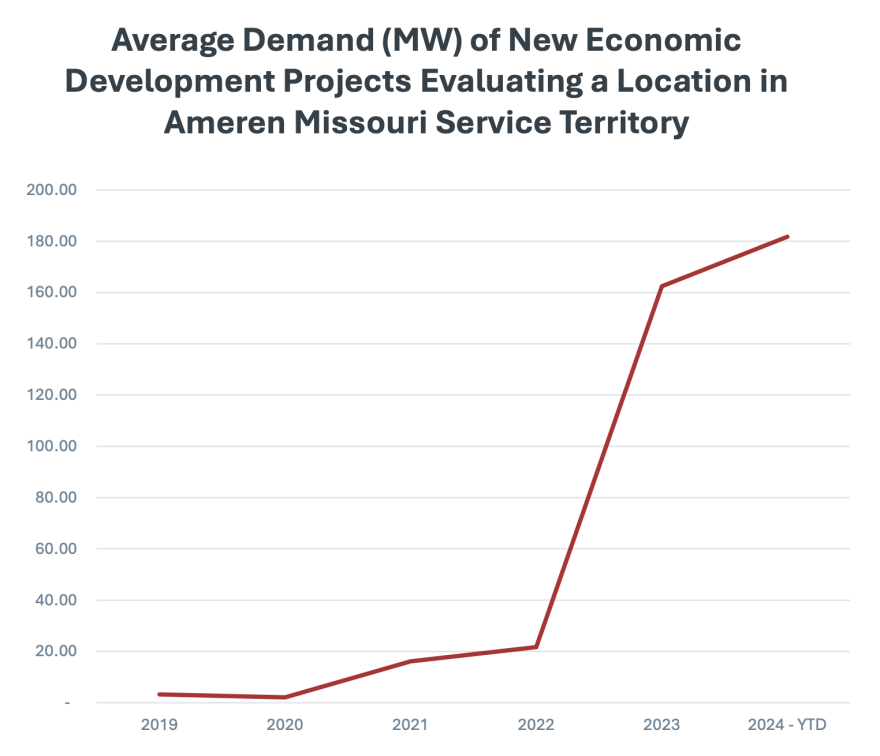

As large data centers consider moving to Missouri, they are asking for unprecedented amounts of energy. At the October summit, state policymakers and business leaders discussed how they would meet the demand.

Gov. Mike Kehoe urged the attendees to figure it out, saying energy is the most important factor for growing Missouri’s economy.

“Not just a data center, it could be any economic development project that we're talking to, that still is our No. 1 question, ‘What can you do for me for reliable base load power?’” Kehoe said. “And so I implore upon you to help us move that ball down the field.”

But with the data center-driven push for more electricity, experts say there is a real risk that regular people will see their electric bills skyrocket because the decades-long precedent for how monopoly utilities make money wasn’t built for customers that are potentially 60 times larger than the current biggest energy consumer on a system.

Incentives to build

The data center boom is particularly enticing for monopoly utility companies because they make money by building things, said Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard Law School and co-author of the paper “Extracting Profits from the Public: How Utility Ratepayers Are Paying for Big Tech’s Power.”

“Utilities have a peculiar business model where their profits are tied to how much money they spend on physical infrastructure,” Peskoe said. “So the more power lines and power plants they build, the more profitable they are.”

A single data center can use as much power as a large city, which Peskoe said means utilities will need to build a lot of new, expensive infrastructure.

On top of that, Peskoe said investor-owned utilities like Ameren Missouri have an incentive to tell shareholders they are going to be building soon, and thus bringing in more profits.

“Ameren is a for-profit company,” Peskoe said. “It has a stock that trades on a stock exchange, and some of the information that it puts out is designed for investors and potential investors.”

In its Aug. 1 call with investors, Ameren said that it had a “robust data center pipeline” and that its sales growth in the coming years would be primarily driven by increased data center demand.

Ameren said it had about 2,300MW of signed construction agreements with data centers, and previous public filings by the company said those agreements represented five projects. The company’s CEO, Marty Lyons, also said these prospective customers have already paid Ameren millions of dollars.

“These developers have demonstrated their confidence in and commitment to their potential projects by submitting nonrefundable payments totaling $28 million towards the cost of necessary transmission upgrades,” Lyons said.

The company would need to quickly accelerate the building of power plants for new customers, Lyons said.

Along with a business model that incentivizes construction, utility companies like Ameren also typically spread the cost of building power plants and other infrastructure out among all customers through rate increases, Peskoe said.

“So in effect, utility profits go up, and everybody's bills go up as well,” Peskoe said.

Risk of overbuilding

Peskoe also said a huge risk is that utilities will build power plants for data centers that don’t move to their areas.

“There's a possibility that we're in a bubble right now, and if the utilities do build out a lot of new infrastructure, and the data centers never show up or they use less power, the utilities may very well go to regulators and say, ‘We want everyone else to pay for this infrastructure that we thought was going to be paid at least in part by the data centers,’” Peskoe said.

As these companies shop for a location, they are talking to multiple utilities in various states, which presents the risk that the projects are being double-counted in energy planning. The Sierra Club found more than 700GW of data center claims from U.S. utilities, which would represent more energy than the entire country produced in 2024.

At the October energy summit, multiple speakers said Missouri is competing with other states to win data center contracts. During a question and answer session, Hataway, the director of economic development, was asked if this might represent a bubble that would burst.

“Honestly, everything is cyclical, right?” Hataway said. “So I'm not going to sit here and tell you guys that there's not going to be potentially a boom with regards to data centers, right, and the bubble burst, right?”

But she said the size of investment from the companies signaled long-term commitments.

“I would ask, do we want to take advantage of the opportunity as it's happening?” Hataway said. “I'm not saying we have to take advantage of 100 data centers that are looking at Missouri, but do we be extremely picky?”

Protecting other customers

One way to keep regular people from paying for data center infrastructure is by designing special rates, called tariffs, for the huge customers, Peskoe said. There is a movement to do that across the country.

Missouri’s legislature passed a law this year that requires utilities to write tariffs for customers demanding 100MW or more of energy.

“That's a good step to kind of isolate these data centers from everybody else,” Peskoe said. “But the devil really is in the details.”

Ameren has written its proposal for these rates and submitted it to the Public Service Commission, which regulates monopoly utilities in Missouri. The company’s leaders have said they want to both protect existing customers and attract data centers to the region.

“We're going to do everything that we possibly can to reasonably ensure that these customers are paying their fair share, and that we're not unjustly passing costs on to other customers,” Rob Dixon, Ameren’s senior director for economic, community and business development, told St. Louis Public Radio in August.

At the October energy summit in Missouri, Ameren’s senior vice president who oversees data center customers, Ajay Arora, said the company is focused on making sure everyone is paying a representative share and the most vulnerable customers are protected from data center costs.

“We just have to make sure that we allocate capital in the most optimal manner to find the exact places which have the most value to customers,” Arora said. “And that's what we do, while also ensuring that we're negotiating hard, we're planning the supply chain, we're ensuring we're keeping costs low for customers, but most importantly, that we are keeping the operating and maintaining costs as low as possible.”

On the August earnings call, Ameren CEO Lyons also said the construction of data centers and more energy infrastructure will benefit everyone by creating jobs and tax revenue that support the local economy.

“To realize this opportunity, we must also offer attractive rates,” Lyons said.

In the initial proposal for data center tariffs, Ameren laid out a base rate of $0.06 per kWh, which is similar to the bulk rate other industrial customers currently pay. Residential customers pay $0.16 per kWh in the summer.

Ameren’s proposal for data center customers also includes terms to try to isolate costs and prevent overbuilding, like a minimum 15 years of service, exit terms and fees, a minimum energy use of 70% of what the data center asked for, and credit or collateral requirements.

While Peskoe said these tariffs are common sense, nailing down rates is always a contested process that is ultimately up to Missouri’s Public Service Commission.

“There's a lot of calculations that are going to go into determining what the rate structure ought to be,” Peskoe said. “And this is not a physics problem that ultimately has a single right answer.”

And Peskoe said it will be difficult to know the actual amount data centers might add to regular people’s bills.

“There's a long history in this industry of hiding a lot of information from the public about the utilities future plans and about how it computes its rates, and it's going to be challenging to figure out exactly how much costs these facilities are adding to rate payer bills,” Peskoe said.

In September, Missouri Public Service Commission staff called on the body to reject Ameren’s data center proposal. They calculated that a single 100MW data center would raise the bills of existing Ameren customers by about $22 million every year until the data center’s new load was accounted for in a rate case. An Ameren spokesperson said the company disagrees with the staff’s position.

Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., sent a letter to Ameren CEO Lyons on Wednesday demanding information about utility bill increases and data center costs.

“Missourians deserve affordable and reliable electricity,” Hawley wrote. “They should not be forced to subsidize corporate projects while struggling to keep their lights on.”

Ameren expects a decision about its data center rates from the Public Service Commission by February.

Ari Peskoe spoke with STLPR’s Kate Grumke on St. Louis on the Air. Listen to the conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube or click the play button below.