Super bugs — those bacterial diseases that are resistant to antibiotics — are growing, according to a recent World Health Organization report. Not only are the bugs getting stronger, the report explains, but pharmaceutical companies are also not developing enough new antibiotics to replace the ones that become ineffective. As a result, patients are suffering as the arsenal of antibiotics to fight infections dwindles.

Hazel Watson is one of those people.

Watson has been battling recurring urinary tract infections for years. She recalls the day the antibiotics she had been relying on stopped working: "I remember my husband trying to call me. And I heard the phone ring, and I couldn't answer it. I couldn't move. Then he came home from work, because he knew something was wrong."

Watson was dangerously sick. She became comatose. Her husband rushed her to a local hospital. Watson's infectious disease doctor, Erik Dubberke of Barnes-Jewish Hospital, explained that Watson had to be ventilated and was on medication to maintain her blood pressure. She came very close to dying, he said.

There's still one antibiotic that can fight Watson's infection. But Dubberke cautioned that if the bacteria become resistant against this last antibiotic, Watson may be out of options.

Antibiotic Discovery And A Deep-Cold Freezer

Professor Tim Wencewicz is trying to help patients like Watson. In his lab at Washington University in St. Louis, he works to develop new antibacterial medicines. It's safe to say that Wencewicz is a chemistry nerd. He carries three different pens on him at all times just in case, he says, a sudden inspiration for a new antibiotic structure strikes.

Wencewicz's lab is new — there's still plastic wrapping on some of his equipment. But one item in his lab is quite old: a -80 degree Celsius freezer.

The freezer was a gift from his post-doctoral mentor at Harvard University. It holds a rare library containing 10,000 strains of frozen bacteria discovered from the last few decades. Researchers across the country email him, asking for samples so they can study and develop new antibiotics.

Accomplishing that goal is getting tougher, said Wencewicz. He outlined two reasons: The science is challenging and the economics is getting nearly impossible.

Scientific challenges: Aiming for an evolving target

Wencewicz said that when it comes to developing antibiotics, the easy stuff has already been done. He referred to the 1940s through 60s a kind of golden era. "We had so many of these so-called magic bullets that could kill every known bacterial infection," said Wencewicz.

But bacteria constantly evolve and develop resistance against those "magic bullets." According to Wencewicz, resistance can develop immediately: "That is just the nature of antibiotics. You can see resistance within the first year of use in a hospital.

An expensive undertaking

Coming up with new antibiotic structures is both tricky and expensive, said Wencewicz. It's a problem because antibiotics are cures. Patients take them for a week and then are done. It's not like the big, money-making drugs such as the blood-pressure pill, Lipitor, that people take everyday for the rest of their lives.

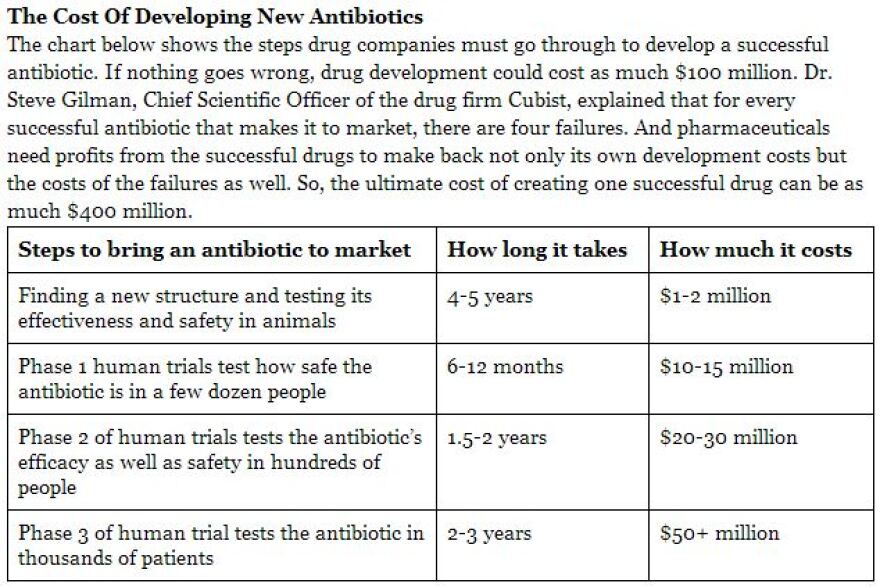

Wencewicz also explained that antibiotic resistance only adds to the business challenge: "On average it costs $1- to 3-billion to develop a drug. But you see resistance within a year. And potentially within 2-3 years, your drug is no longer useful. And there's no way to make back your original investment."

Hope despite drug-resistance

But there is one drug company that may have one solution to the drug resistance problem. The pharmaceutical company Cubist has what can only be called a "blockbuster" antibiotic: Cubicin. It's remained effective for more than a decade. The secret, according to Cubist's Chief Scientific Office Steve Gilman, is that the drug is only given to 13 percent of patients that could get it.

"Every time you use any antibacterial in patients where the drug is not effective, you have a chance to develop resistance," Gilman said.

A hopeful future

Patient Hazel Watson is grateful for the one antibiotic she has left, and she's hopeful. The 60-year old explained that she's survived cancer and getting liver and kidney transplants. "There's so many things that have nearly killed me," she said. "I figure, I made it this long. I'm pretty hard person to kill. So I'm going to be optimistic that I'll get through this too."

There may be reason for Watson to be upbeat. Researchers are looking in new, unconventional places — such as caves and in the Arctic — to come up with more antibiotics.

Follow Jess Jiang on Twitter: @JiangJess