It’s not as if everyone were oblivious to the architecture of the middle of the 20th century in St. Louis before current interest in it took hold. Prominent mid-century landmarks that are, or were, part of our regional consciousness: the Saarinen Arch, certainly; Samuel Marx’s Clayton Famous-Barr building on Forsyth Boulevard; the Teamster’s complex on Grand Boulevard, with the space-agey former Phillips 66 station enjoying new life as a Starbucks and Chipotle restaurant, and until recently, Edward Durell Stone’s mid-1960s Busch Stadium.

Nevertheless, many who are more or less keen on and appreciative of the beauty and variety of our built heritage have gained a clearer awareness of the richness of the inventory of fine buildings dating from the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, and the danger many of them face in an age of gratuitous tearing-down. This modernist assembly is robust and exciting and strikingly diverse, and taking pleasure in it is part of an aesthetic awakening.

Some of the names of the architects and designers are familiar: Bernoudy, for example, endures as a brand name and a gold-standard Realtor vocabulary word. Other architects are bold-faced in a rich glossary of strength and accomplishment and enduring quality.

Thanks to the work of architect Jessica Senne, assistant professor of interior design at Maryville University, another set of names have been added to this distinguished list. They are Ralph and Mary Jane Fournier, both graduates of the Washington University School of Architecture and both architects of vision. What Bill Bernoudy did for well-heeled clients the Fourniers did for families of more modest means who, apparently, appreciated dwellings of style and authenticity. Senne has organized an exceptional exhibit of their work, on display in Maryville University’s Morton J. May Foundation Gallery through Feb. 22.

Modernist in Crestwood

The Fourniers worked in primary association with St. Louis developer Burton Duenke. For Duenke and his company, the Fourniers designed modernist houses that provided flowing space for the communal lives of families, and cozy, intimate spaces for privacy and for sleeping.

Ralph Fournier, now in his 90s, recalled that early in his association with Duenke the houses were “traditional,” but soon, a modernist turn was made at the drafting table. In an essay for the newsletter of the Landmarks Association of St. Louis, Jessica Senne outlines the move toward modernism and how in the Fourniers’ hands and with Duenke’s patronage and commercial encouragement the enterprise thrived.

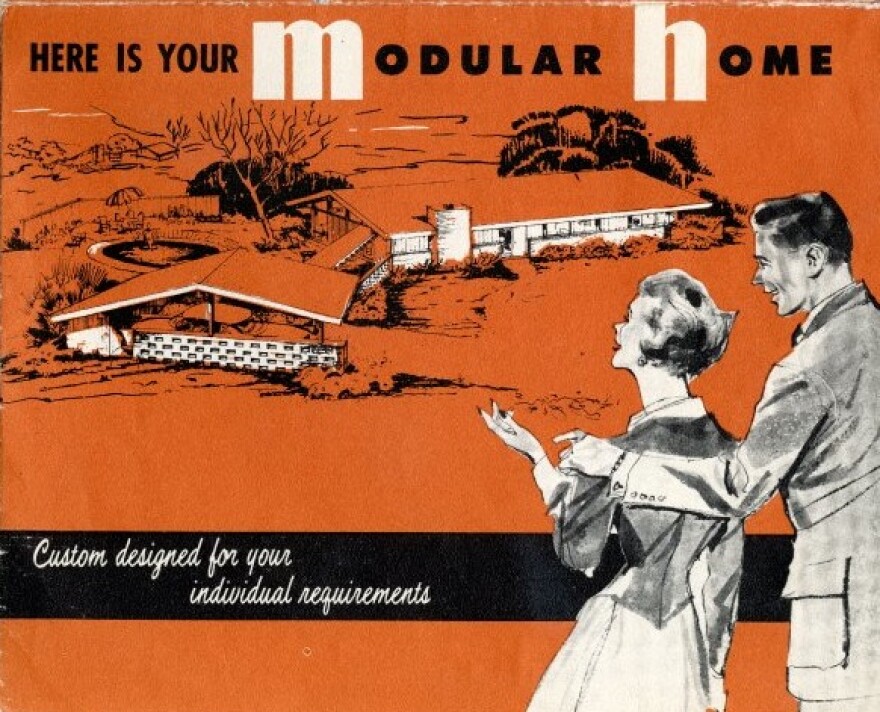

The first modernist “neighborhood” was called Ridgewood. All these houses and houses to come in this Crestwood area were post and beam construction, basement-less and framed by prefabricated wall panels manufactured in St. Louis. Ample fenestration created an airy atmosphere bathed in natural light.

Ridgewood received respectful press coverage and was a hit with homebuyers in the housing-crisis post-World War II environment. A three-bedroom, bath-and-a-half, Fournier-designed, Burton Duenke home sold in the early 1950s for $14,400.

In a telephone interview, Ralph Fournier said when the modernist work for Duenke began he immediately got rid of trusses, creating a lower-pitch, on-member roof and ceiling.

Fournier said modernism was in the air, and his desire was to design residences that were at once functional, stylistically interesting and visually arresting. He and his wife bought and moved into a Ridgewood house in 1952, he said. Two sons were born soon after the house was bought. The family built a kidney-shaped swimming pool and lived there for five years. Fournier also designed a much grander house for Burton Duenke on a six-acre site overlooking the Missouri River.

Besides modernism’s being in the air, there was the excitement with the home-grown American architecture of the Prairie School, dominated by Frank Lloyd Wright, and fresh, rationalist ideas espoused by architects such as Richard Neutra, Albert Frey and Rudolf Schindler. Others, such as the egalitarian California architect Joseph Eichler, brought to American architectural practice a commendable sense of social responsibility. Burton Duenke and the Fourniers fit neatly in the Eichler tradition, which was built on a belief that good design need not be exorbitantly expensive and that the middle class deserved comfortable, loveable, manageably priced dwellings.

A revealing exhibit

In the exhibit at Maryville, Senne makes this intention clear in a most revealing show, one filled with not only with an abundance of illustrations, drawings and photographs but also a reconstruction of a Fournier module.In an interesting way, Senne and her husband, Aaron Senne (also an architect), are practicing what she preaches in her Maryville exhibit. They bought a Fournier house in the Sugar Creek Ranch neighborhood in 2012. Following a six-month renovation, they moved in and live there now with their son, Arlo.

“Architecturally,” she wrote in an email to me, “we love so many things about our house here in Sugar Creek Ranch. We love that the entire house is on one level - we have no basement and no upper level and we do not miss either one. The previous owners lived here about 40 years, and it is evident that these houses are quite suitable for populations that wish to ‘age in place.’ We love the open floor plan our house offers - the entryway, dining room, kitchen, and living area are spacious and flow freely into one another. These public spaces of the house are arranged around a centrally located, double-sided fireplace that provides warmth in the space and also visual connection between the various rooms …

“We were also drawn to the modern use of natural materials and the ample natural light in our house. The fireplace is clad in sandstone and wood paneling, and both bring warmth and texture to the interior material palette. And the large, north-facing windows in our living room provide ample indirect natural light and offer a view of the neighborhood that is always changing with the seasons…

“This connection to the landscape is also something Mr. Fournier explained in past interviews as quite deliberate with the design of the houses. … The combination of high ceilings and open floor plan provide for a house that feels quite spacious even though our entire footprint is only about 2,000 square feet.”

Together, the Sennes’ personal domestic experiences and Jessica Senne’s exhibit provide a glimpse of a fascinating moment whose vitality endures. This is architecture at its most dynamic – functional, beautiful and pedagogical.

By observing the world of the Fourniers in mid-century, and of the Sennes today, we learn lessons about economy and taste. Altogether, this sense of thrift and appreciation of the rich legacy of modernist design presents a rebuke to the vulgar excesses and wastefulness of the McMansionist anti-aesthetic. The Fourniers, Burton Duenke and the Sennes speak an architectural language that celebrates beauty, efficiency and responsibility, and offer us a sensibility worth examining as we move forward in a world in which resources of all sorts diminish dramatically every single day.